“Harvests of Hope: Celebrating the Spring Feasts in the Hebrew Roots Tradition”

The spring season in the Hebrew Roots movement is a time of profound spiritual significance, marked by several feasts that are rich in symbolism and historical importance. These feasts are typically determined by the agricultural and lunar cycles, as per the traditions and scriptural interpretations within this movement. Here’s an overview of each feast, capturing their essence and timing:

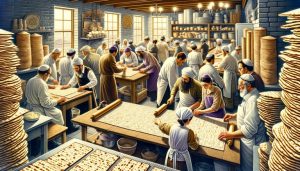

1. The Feast of Passover (Pesach): This feast commemorates the Israelites’ liberation from Egyptian bondage, as recounted in the Book of Exodus. It begins on the 14th day of Nisan, the first month in the Hebrew calendar, which is set by the sighting of the new moon and the condition of the barley being ‘aviv’ or ripe. This usually occurs in March or April. During Passover, unleavened bread (matzah) is eaten to remember the haste with which the Israelites fled Egypt, not having time to let their bread rise.

2. The Feast of Unleavened Bread (Chag HaMatzot): Immediately following Passover, this feast lasts for seven days. It serves as a reminder of the purity and simplicity of life that should characterize those who have been redeemed. The removal of leaven from the home during this period symbolizes the separation from sin and the pursuit of holiness.

3. The Feast of Firstfruits (Yom HaBikkurim): Occurring during the week of Unleavened Bread, this feast is a joyful celebration of the early spring harvest. It involves presenting the first sheaf of barley to Yehovah as a symbolic gesture of dedicating the upcoming harvest to Him. This feast is also seen as prophetic of the resurrection of Yeshua, whom believers view as the ‘firstfruits’ of those who have fallen asleep.

4. The Feast of Weeks (Shavuot or Pentecost): Occurring fifty days after the Feast of Firstfruits, this feast marks the end of the barley harvest and the beginning of the wheat harvest. It also commemorates the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. This dual significance – both agricultural and historical – makes Shavuot a time for both thanksgiving and reflection on the law of Yehovah.Each of these feasts, while rooted in the agricultural calendar of ancient Israel, is given a renewed and deepened meaning in the Hebrew Roots movement. They are not only historical commemorations but also prophetic in nature, pointing to the work and person of Yeshua and the ongoing work of redemption in the world. These celebrations offer a time for reflection, thanksgiving, and communal joy, deeply connecting the participants to their spiritual heritage and the rhythms of the natural world.